21. November 2025

Diedrich Diederichsen

21. November 2025

Diedrich Diederichsen

On the occasion of the exhibition TURNING PAGES: Artists’ Books of the Present, on 30 September 2025 the renowned essayist, cultural critic, curator, and journalist Diedrich Diederichsen spoke in the MAK on the aura and communicative dimension of the artist’s book. His lecture may now be read in its entirety in the MAK blog.

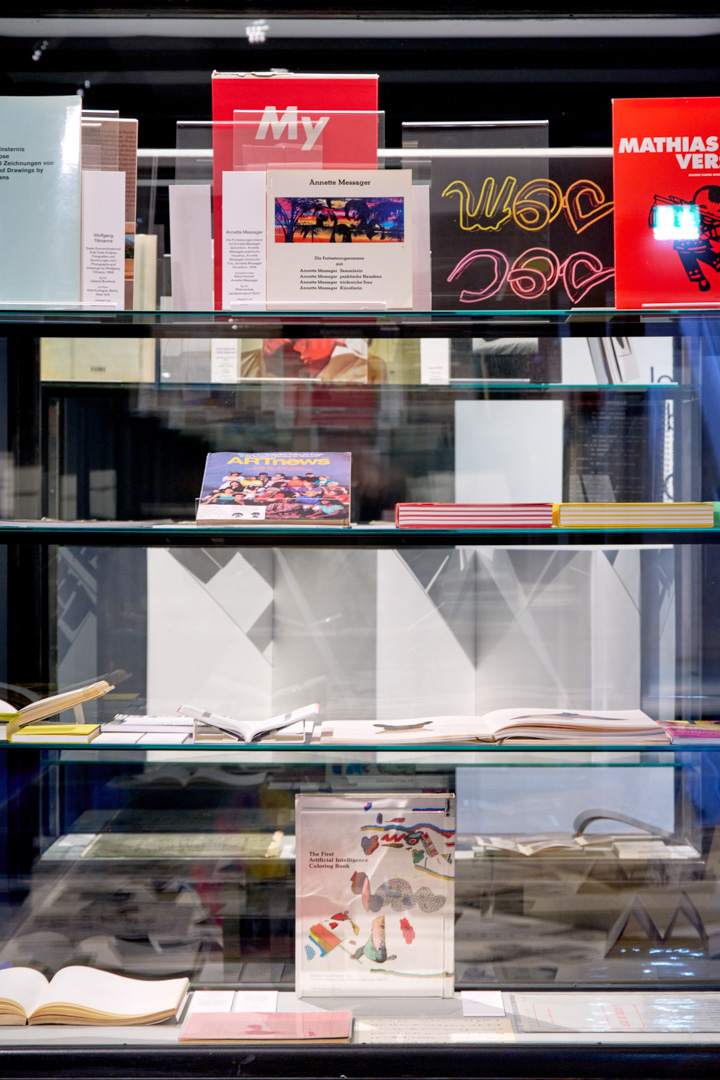

MAK Exhibition View, 2025

TURNING PAGES: Artists’ Books of the Present

Central Room MAK Design Lab

© MAK/Christian Mendez

I don’t know what qualifies me to talk about artists’ books—as far as I can recall I’ve never published anything on them. However, the first seminar I ever taught, in the winter semester 1992/93 in Stuttgart, was on precisely this subject—more of which later. Also, from the days of my youth I have a memory of a culture center that—although back then the term did not exist in my social circles—stands for a historical context that more accurately defines the artist’s book as genre than the technical and contextual attempts that I will nevertheless undertake after I’ve narrated this memory.

Diedrich Diederichsen, 30 September 2025 at the MAK

© Julia Dragosits

Although she wasn’t really a bookseller by education, in the 1970s the artist, author, and activist Hilka Nordhausen ran a store in Hamburg’s Karolinenviertel, back then a neighborhood of just a few—maybe four or five—blocks that was still completely in bohemian hands. It was bordered on one side by a trade fair arena, on another by a slaughterhouse, and on a third by the Heiligengeistfeld, a cotton candy quarter akin to Vienna’s Wurstelprater amusement park, although the FC St. Pauli also plays there. Her shop bore the name “Buch Handlung Welt” [Book Shop/Story/Action World]. It was not so much a bookshop named “World” but all sorts of things—art gallery, event venue, and also bookshop—with a name made up of the three nouns: “Buch Handlung Welt.”[1] It had three main lines of business: first, self-published literature or literature published in small editions by Beatnik authors or their successors—people like Ted Joans—who often came by to read their works, or Jürgen Ploog, the acid-dropping man of letters and Lufthansa pilot, or Natias Neutert. Everything in this first category had to do with books, with literary publications. Secondly there were the periodically fluctuating wall paintings and other activities by contemporary young artists from Anna Oppermann to Albert Oehlen. And finally, there were the self-published, hectographed—later photocopied—magazines such as Boa Vista and Henry, and other publications by authors, artists, and above all filmmakers of those years. This was all happening historically just minutes before punk arrived on the scene. Only a few days, weeks, months later, diagonally opposite “Buch Handlung Welt” a pub called “Die Marktstube” [Market Lounge] opened, run by a man who makes quite a few appearances in Hubert Fichte’s novel Die Palette. This pub became a punk hangout and “Buch Handlung Welt” also began to have punk fanzines and pamphlets on offer, bought by kids on average ten years younger than its regulars. This all goes to illustrate how as wide-eyed young visitor to these places I began to realize that—and how—a certain way of publishing had to do with its content and social consequences—even though the media, genres, and sense organs their creators worked with varied greatly. This mingling of milieus was thus possible—and a minor triumph of utopian endeavor. Artists’ books as a genre stand for a similar blend of milieus, each with its well-rehearsed communication and artistic formats.

Now there’s a wide range of objects that pass for artists’ books, from somewhat excentric—though actually completely normal—institutional catalogs, in which the artist has to some extent influenced the graphics, to bizarre publication projects located in grotesque containers constructed of absurd materials, on some of which a few words have been inscribed: for instance on a flexi disc, or some gibberish or other stamped inside a carton together with glass wool. The classic disciplines of the fine arts were apparently just as absent from the neighborhood as was poetry—but what else could this be? And then there are those books on your shelves not published by regular publishers but as small handmade editions in printings of 30, maybe even with each copy hand-colored differently. But the texts they contain are completely normal poems or essays, such as you could find in completely normal publications. At the beginning of this century in Argentina, there arose an entire literary activist movement. In solidarity with so-called cartoneras and cartoneros—people who to survive the never-ending economic crises collected wastepaper and flogged it to urban collection points—this movement published small editions of hand-made books made of recycled wastepaper collected by the cartoneras. The country’s top authors joined this movement, contributing exclusive texts—for instance César Aira. The very limited editions guaranteed higher prices, to the benefit of the cartoneras.

MAK Exhibition View, 2025

TURNING PAGES: Artists’ Books of the Present

Central Room MAK Design Lab

© MAK/Christian Mendez

MAK Exhibition View, 2025

TURNING PAGES: Artists’ Books of the Present

Central Room MAK Design Lab

© MAK/Christian Mendez

Each definition of—and thus each discussion about—artists’ books must live with the fact that the boundary—the finis hiding in the word definition—to catalogs, limited editions, multiples, works on paper, is blurred. But this blurredness is also part of the specific potential of this genre or anti-genre. For it expropriates the strengths and strategies of practices located on the periphery but unanticipated in the centre, thus undermining the distribution of the sensible and of reception in a way diametrically opposed to today’s digital dissolution of boundaries. This protest against the distribution of the sensible takes place not via a smoothly running, disruptive TikTok metavisuality but by concretely acknowledging specific traditions that are than attacked, expanded, or negated.

If on the other hand one tries to narrow down or delimit the subject of this exhibition from the perspective of milieus or traditions, there are some specific traditions, including pop music fanzines and other popular cultural phenomena; the small presses of the Beat Generation; the Samsidat culture that flourished in the countries of real existing socialism (and that survived by printing small editions because the authorities were interested only in censoring editions in the upper two-digit or three-digit range); naturally the manifesto and proclamation culture of avant-garde movements; and movements such as Mail Art that has evolved a special theory of addressing—something that this presentation will enlarge on later, and one which Internet pioneers were to take up.

All these are collaborations and projects for whom the decision to publish in small editions—to avoid the extremes of unique originals and industrial production methods—has very different rationales. It is small wonder that classification and categorization in the entire field here under discussion starts out from the archive, where sooner or later the stuff ends up, thus imposing archival categories both on collectors and on those whom the institutional consequences of collecting compel to conceptualize.

When in the early 1990s I worked with students who considered themselves in the broadest sense to be communication and graphic designers, but who were massively confronted with the question of those years as to whether artists too should consider themselves service workers and designers, the history of artists’ books was a source of inspiration. The discussion being conducted back then concerning the difference between free and applied, autonomous and heteronomous art—in the context of a crumbling, crisis-shaken artworld threatened by repoliticization—was also relevant to the situation of critical designers and seemed to bridge a gap. But what had already become apparent even then was that the specificity of artists’ books was derived not so much from their particular materiality but from the distance they cover in cultural space: who creates them and where, using what technical and economic resources—and where they finish up, whom they reach.

Well, first of all they obviously finish up in the archive, because that’s where I found them—together with the term used to designate them and the necessity of using such a specific term at all. On the one hand, there was the Sohm archive in Stuttgart, and on the other that of the Walther König bookshop in Cologne. Sohm, who was born in 1921 and died in 1997, was a Swabian dentist and for many years a leading Fluxus art collector and expert. In 1970, together with Harald Szeemann he participated in creating the important Cologne exhibition, and its accompanying catalog, Happening & Fluxus.[2] After the heyday of Fluxus, roughly the 1960s and early 1970s, he continued his activities as collector, acquiring objects and documents dating from both before and after this period and originating from locations not associated with Fluxus (such as New York and the Rhineland). One can say that as collector he extended the boundary-defying practices of Fluxus to other epochs, without presupposing the specific mentality and nomenclature of Fluxus artists. Another category was needed, at the latest when in 1986 Sohm’s own collection was presented in a comprehensive exhibition at the Nationalgalerie in Stuttgart and a first major catalog appeared.

The catalog bore the title Fröhliche Wissenschaft,[3] the title of a collection of aphorisms published by Friedrich Nietzsche in the 1880s, and in turn taken from the name of a group of 14th-century Provencal poets: the “Gai Saber”. In most languages Nietzsche’s title is translated as “Gay Science”, “Gaya Scienza” or similar. Nietzsche himself used the Italian translation as subtitle of his book. Meanwhile in some English translations the title “Joyful Wisdom” is used since “gay” now has other connotations. These entanglements—gay, joyful, science, wisdom—is of course a very relevant demarcation of the starting point from which to address the phenomenon of the artist’s book. In 1968 Jean-Luc Godard made his first fully experimental dialogue-driven film Le Gai Savoir, in which a fictional descendent of Jean-Jacques Rousseau converses with a fictional daughter of Patrice Lumumba. Here too, the point was to dissolve the distinction between fictional narrative and argumentative discourse. Nietzsche, on the other hand, insists on what he calls the unity of “knight, singer, and free spirit” in the tradition of medieval Provence. Let’s take these fun facts as proof that the establishment of the artist’s book as object beyond concretion in the Fluxus scene triggered epistemological and sociological crises and upheavals that functioned as inspiration, endorsement, and role model.

The Stuttgart Staatsgalerie then took over the Sohm collection and initiated a series of publications on the Sohm archive which—as far as I know—did not get beyond a first volume entitled Art Games. Die Schachteln der Fluxuskünstler [Art Games: The Fluxus Artists’ Boxes], part one, 1997. Back then I and my students also visited the legendary archive/museum of the Walther König bookshop in Cologne, on the first floor over the store itself. However, this archive—accessed at our request—supplied no conclusive definition of what constitutes an artist’s book. Though it did manifest a certain pragmatism: publications from the fine arts and related contexts—related through guilt by association—that possessed a certain rarity and thus a certain monetary value, were kept behind glass on the first floor. For us researchers they could thus be classified as “artists’ books.” I’d like to start out from a slightly modified form of such pragmatism to extrapolate two categories which may serve to define very many artists’ books—in order, in a further step, to raise the issue of the address and thus establish a more precise media-theoretical category. But in the last analysis the—in many ways peremptory—suggestion of Kellein and Sohm ought to be accepted in presenting a sketch of a gay science or joyful wisdom—peremptory in the sense that it is not the salvation, the creativity, or the spontaneistic insubordination of the researchers that necessitates such a suggestion but the subject itself.

But first a distinction that concerns the social, economic, hierarchical, and political relationship of artists’ books’ creators to art and/or literature’s public sphere. There exists a tradition of inadmissible publications, and there exists a tradition of more or less established ones. The first group looks after its own; this includes the fanzine, small press, cartonera and samizdat traditions. They attack the established distinction between on the one hand the public and on the other—as applicable—the clandestine, exclusive-elitist, or auratic-singular tradition not (only) out of conviction but out of necessity. As in innumerable other media and media practices of the postwar period, what was perforce materially/socially excluded is transformed into the stuff of art, just as was later—after Punk and the “Geniale Dilletanten”—what was perforce technically defective. Any suggestion of these inadequacies is transformed into a vigorous new mode of expression. You can see this in both the Beatnik poetry of the 1950s and the way guitars are treated in 1978. The difference between so-called artists’ books and Punk is that the former’s design of media, books, flyers, etc. does not operate within traditional fields of expression that they then attack by not sticking to the rules. Instead, they expropriate resources—layout, typography, binding, etc.—traditionally regarded as support in the background, that simply allows the foreground to be developed unobstructed.

But the result of this assault on the support structure and its supposed neutrality is that not only do the cheap materials, printing methods, and inadequate technical skills being used stand out. The assault also subverts the division of labor into figure/support, carrier/content, signifier/signified, i.e. the institutionally conventional framework that—even before the familiar distinction between form and content—makes the latter distinction possible in the first place. But at this deconstructive point, the fanzine meets up again with the catalog, or with the institutionally anchored artists who’ve developed an interest in the history of art publications, such as Dan Graham, Eleanor Antin, Marcel Broodthaers, Sanja Iveković, Dieter Roth, Martin Kippenberger, Hanne Darboven, Ed Ruscha, Ferdinand Kriwet, and Michael Krebber. In many of the abovementioned’s works, created mostly created between 1970 and 1995, the point is also at least to historicize the catalog as construct—as a supposedly neutral, supportive, generic resource—if not to question its existence absolutely. Although equipped with more resources, in these books too the attack is directed against the neutral or supportive function of art presentation—for instance when Kippenberger cites a catalog title picture by Germano Celant, or in his book Die I.N.P.-Bilder [The I.N.P. (= It’s Not Embarrassing) pictures] parodies a whole catalog by Walter Dahn and Georg Dokoupil. The task of determining the framework and institution—and likewise their critical relativization—becomes the responsibility of the artist.

Yet relativization and critique take place on the second level—through imitation, parody, discreet shifts, clever citation or contradiction; whereas on the first level they tend to take the form of laceration and rupturing, of the subversion of standards or of outbreaks of a largely less sophistic fantasy. A special case of this first level is the use of what were considered back then to be vulgar, low-life milieus and their media. The Olympia Press, that in the 1960s published the forbidden books of Genet and Burroughs worldwide, as well as other Beatnik titles, also published trash crime and porno novels. The authors published by Olympia willingly accepted the nimbus of triviality; comics and pulp fiction too were already important trend-setters in the pre-Pop era, especially when Pop artists such as Claes Oldenburg began to produce their own comic books.

Of course, these are very generalized distinctions, yet I’d like to add a further one before I turn to the question of addressing, namely those artists’ books that by all means fit a vague, rough-and-ready definition of the genre but that were created after the time when you still had to cling to the ideal of an artist’s position relevant to and responsible for literally everything. In this situation, the point was no longer to deconstruct the support/work, carrier/content dichotomy; rather you could position the printed and duplicated objects as supports for an all-over of these all-encompassing artists’ positions. Isa Genzken has produced such books, for instance. Here ‘all-over’ does not imply a relapse into a carefree age in which supports were ignored but rather that precisely those media and processes—problematic for such a position because not immediately available—such as those related to printing or duplication, were treated as if they were indeed directly accessible. The technique of collage is of course the ancestor of such books.

A final, still missing category is derived from the Artistic Research movement—or boom. If I consider artistic processes themselves as guiding research and am also interested in reaching out to a community of discourse, then artists’ approaches to books and paper, and to forms of reproduction, are a good place to start. Artists who prepared the ground for the institutional boom in Artistic Research and its concomitant terminology, such as Alan Sekula, published their socio-artistic conclusions in book form. Later publications by artistic researchers themselves also parodied or subverted the style of scientific publications—while not foregoing publication of relevant material.

AK Exhibition View, 2025

TURNING PAGES: Artists’ Books of the Present

Central Room MAK Design Lab

© MAK/Christian Mendez

MAK Exhibition View, 2025

TURNING PAGES: Artists’ Books of the Present

Andy Warhol, a: A novel, 1968

Central Room MAK Design Lab

© MAK/Christian Mendez

To summarize at this point: we have here to do with publication projects that are, firstly, poetically underfinanced, and literature-oriented; secondly, deconstructive, allusive, and somewhat fine arts-affined; thirdly, liberated, post-conceptual and fine arts-affined; and finally, research-oriented and hybrid. But if you consider the extremely long, impressive, and of course potentially extendable list of items in this exhibition, you must conclude that a very large number of the objects on display subvert these distinctions— distinctions that were in any case retrospectively developed—thus creating hybrids. The secret of knowing what we mean by artists’ books does not have much to do with establishing good categories—and is also not to be explained by timely practice in our youth.

A traditional polarity exists in the production of cultural objects—at least in pre-digital times, and in a certain sense even now. At one end of the scale is the auratic original, a unique creation, and at the other the mass-produced, duplicated printed object. As regards duplication, it is initially irrelevant how large the edition is—even though it may be for later valuations. What is decisive is only the status of the copy that a machine has produced, whereas the original not only bears the mark of the “master” but in addition is completely accessible to only one person in the world, is addressed to one person alone—namely (except when given as a gift) the purchaser. Even in the case of multiples or limited editions, located somewhere between the extremes of this polarity, the person addressed is usually a singularity, an individual case—even when there are now more of them. The multiple is a duplicated original; it is not a mass-produced object of which only copies exist.

But this polarity is, as you see, defined by two parameters: on the one hand by the distinction between specific works produced in small quantities versus mass production, but on the other by the question of addressing. This indeed corresponds to the first distinction in the sense that the original is specific: Nevertheless, it is not—in contrast to works from the Age of Chivalry—made for a specific purchaser but for an arbitrary one—though nevertheless only for one purchaser. The mass product, on the other hand, is made for many—who must however pay for it. But mass products always participate in secondary dissemination: songs and popular pictures or faces are disseminated in the sociosphere, even among those who are not directly involved in the act of purchasing. Now every cultural product performs acts of addressing through its design, its artistry, and its content, and every artist knows, without having to waste time on planning or thinking about, that decisions made in each of these areas both exclude and include, motivate and deter, and thus have a social dimension that cannot always be directly transposed to their aesthetic dimension. But it is an entirely different case when this decision is predetermined or framed by the medium or genre itself. When hectographing or photocopying technically limits the size of an edition, and when, furthermore, the genre—for instance the fanzine—assumes a tribal or subcultural identity in its intended audience and addressees, then this intermediate magnitude between mass production and original exists as regards both parameters: address and edition. And the foregoing description, I believe, constitutes a more stable basis for a discussion of artists’ books than if you were simply to deduce characteristics from the wealth of available examples, collate them, and set them up as criteria.

But the addressing of cultural products, and in particular those listed under the fine arts, is a particularly hot topic: are clandestine subcultures at work here, or perhaps an educational elite, an arrogant Bohemia or a self-empowering counterculture? At the latest since the 1990s and the extremely influential reception of Bourdieu’s work in art circles, the double-edged nature of sociodesign through artistic manoevering has been a burning issue. The self-help ethos that seems to play a crucial role in many poetic and fanzine-like projects—the ‘scene-making’ propagated by “Buch Handlung Welt”, worldwide initiatives such as New York’s “Printed Matter”, or the independent press fairs in cities such as Paris and Berlin—seems just as constructive as richly inferential juggling with typeface or virtuoso citing of layout details (to include miniscule deviations from the draft) seems at first sight snottily presumptive and arrogant. At the same time, such presumptive communication of genre details also facilitates an incredible acceleration of perception and understanding. It exercises a sapioerotic attraction on laypeople and paves trails of elegance to their own empowerment—and it is attractive precisely because it is not determined by a real weakness but by a power emanating from the internal cohesion of certain artistic practices in contact with each other.

But in both cases the genre of artists’ books can more precisely formulate addressings than can the other distributive possibilities located at the two aforementioned poles. It records its edition count not in an imprint but in the medial form of its product. Consequently, it’s not a dubious mixture of snotty-nosed educational privilege and the legitimate advantage of fan-based knowledge that is decisive in reaching an address; rather doing so is from the beginning predetermined, set in motion, by the media materiality and sociosphere of the bookstore, the archive, etc. The term aura may suggest a dubious, long-lost quasi-religious dream of immediate contact, but in the imperfectly reproduced aura of those objects (untouched by human hand except by one shoving a sheet of A4 paper into a photocopying machine) is created a technically mediated but equally intense relationship—this time not between a genius and his/her admirers but between users of worldly tools. This flatter, self-organized, project-shaped distribution of knowledge and beauty, so often associated with artists’ books and their genetic relatives—and to a certain degree defining them—is one thing. That a similar development in the digital media has long reached an entropic, dystopic tipping point is a bird of another feather (though sitting in the same tree) and ought not to concern us right now.

Because, as you may in the meantime have forgotten, I had promised you some “joyful knowledge.” And indeed there are some things that I’ve learnt only from artists’ books, things whose knowledge structure is directly related to their publication in artists’ books. For instance, it’s a well-known art-historical fact, often cited in the lexica and Wikipediae of this world, that the term Concept Art appeared for the first time in an essay by Henry Flynt at the beginning of the 1960s; and also that this elucidation of concept-based art differs from the one later championed by Sol LeWitt, Seth Siegelaub’s circle, and Art & Language. Still, the essay by Flynt only makes full sense when you read it in the context of its original publication, namely in a now very famous—in every sense of the term—artist’s book: An Anthology of Chance Operations (1963). Published by Jackson Mac Low and La Monte Young and originally planned as an East Coast edition of a West Coast literature magazine emanating from an expanded Beatnik milieu, it metamorphosed into a creation with countless foldouts, tiny letters pasted onto the pages, drawings that turn out to be musical scores, and so on. The book has the appearance of a very beautiful, though seemingly unmotivated, explosion of creativity. Instead, almost all aspects of this riot of inspired design are necessarily determined by its musical, literary, artistic, performative, and conceptual projects. Besides all the musical scores, it contains many word pieces by for instance Yoko Ono or Young himself—as well as Flynt’s essay, itself a legendary intellectual construction.

You could give it as a talk or reprint it, but it wouldn’t be the same thing. Flynt, mathematician, composer, folk musician, antiracist, and activist—who together with Jack Smith stormed a Stockhausen concert in New York sporting a sandwich board bearing the slogan “Demolish Serious Culture!” because he had heard that Stockhausen had criticised jazz in what Flynt considered racist terms. This same Flynt argued that the so-called Darmstadt school of serial music following Webern—that is the whole of European 1950s compositional music from Boulez to Stockhausen—could not possibly function because it had not found a way of rendering the complexity of its compositions and series audible. He suggests four concrete negations of this Darmstadt school of music: contemporary R&B, African music—for instance by the Baoulé—and minimalistic drones, as practiced by his friends of those years Tony Conrad and La Monte Young—three musical forms that discounted composition in favor of the ritual, the social, and the erotic. His fourth negation really packs a punch: he suggests not negating the complexity of the Darmstadt compositions as such but rather intensifying and enhancing (and thus negating) them, so that their enhanced complexity satisfies his mathematical sensibility. But then there would be no sense in rendering this complexity audible; it would be enough to write it down (that is to publish it in the form of a musical-mathematic artist’s book). This is what he means by Concept Art.

So Flynt’s suggestion is not merely a derivation of legitimacy—the necessity of the artist’s book derived from the spirit of progressive music. Rather his essay becomes the multilayered construct of negation that it is because it derives its plausibility only by being juxtaposed with musical scores, drawings, tables and guidelines. The essay has had an immense influence on many art practitioners and theorists—often with massive time lags. His addressing can be deduced from the names of the participants and their questions, from the work’s bizarre production history, and from the contemporary everyday practice of participants such as Yoko Ono, Jackson Mac Low, and Tony Conrad. This was the “joyful wisdom” of artists that has become partly institutionalized or has triumphed itself to death—or else is still persisting in exactly the same way.

It is working, if you will, on the central problem of contemporary museum and art policy: how can you on the one hand make museums and their contents accessible—lower barriers—and on the other avoid trivializing these same contents? How can you avoid marketing an illusion of comprehensibility—which in any case does not exist in real people but is only an abstract construct of media companies? How can you avoid extinguishing all traces of knowledge eroticism, of the specifics of addressing, that is so decisive in belligerent art forms? The answer lies in the specific communication form of the artist’s book in the broadest sense (including fanzines, pamphlets, and minipress products). For the artist’s book is not institutionally exclusive along class and educational lines but concretely and specifically addresses those who share a particular interest, struggle or obsession. And what is most important: no superordinate sociocybernetics organizes this communication; no algorithm creates this bubble but specific addressing issues in an otherwise contingent, anonymous space—a social soup and not a net, an emulsion and not a molecule, organized as were earlier the big cities: no clientele but the ideal of specific but thrillingly strange, astonishing counterparts. The look, the words, the material traces of this communication: the matter that matters.

[1] See Hans-Christian Dany, Ulrich Dörrie, Bettina Sefkow (eds.), dagegen dabei. Texte, Gespräche und Dokumente zu Strategien der Selbstorganisation seit 1969 [against involved: texts, conversations, and documents on strategies of self-organization since 1969], Hamburg: Edition Michael Kellner 1998; and Diedrich Diederichsen, „Ein paar Figuren …“ [A few figures …], in: Klaus Modick, Mo Salzinger, Michael Kellner (eds.), Humus. Hommage à Helmut Salzinger [Humus: homage to Helmut Salzinger], Hamburg: Edition Michael Kellner 1996.[2] Hanns Sohm, Harald Szeemann, Happening & Fluxus. Materialien [Happening & Fluxus: materials], Cologne/Markgroeningen: Cologne Art Association/Sohm Archive 1970.[3] Thomas Kellein, „Fröhliche Wissenschaft“. The Sohm Archive, exh. cat. Staatsgalerie Stuttgart 1986.

The exhibition TURNING PAGES: Artists’ Books of the Present is on view in the Central Space MAK Design Lab until 22 March 2026.

A contribution by Diedrich Diederichsen, essayist, cultural theorist, curator, and journalist.

The blog article is part of the interdisciplinary Creative Europe project AbeX.

This project is supported by Creative Europe.

The exhibition TURNING PAGES: Artists’ Books of the Present, along with its supporting program and the accompanying publication, is part of the interdisciplinary Creative Europe project AbeX, funded by the European Union.

Views and opinions expressed are, however, those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Education and Culture Executive Agency (EACEA). Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.

I could sense that he was very dedicated.