15. Dezember 2025

Vanessa Joan Müller

15. Dezember 2025

Vanessa Joan Müller

On the occasion of the exhibition TURNING PAGES: Artists’ Books of the Present, curator and author Vanessa Joan Müller demonstrated in her lecture More Than Just Words: Experimental Poetry and Visual Art on 9 November 2025 how experimental poetry expands from the book into three-dimensional space. She explained how language is thus freed from its usual task of meaning-making and how letters and words can assume new significances. The following blog entry The following blog entry is a slightly revised version of the lecture.

Vanessa Joan Müller, November 9, 2025, at the MAK

© MAK/Kathrin Pokorny-Nagel

Vanessa Joan Müller, November 9, 2025, at the MAK

© MAK/Kathrin Pokorny-Nagel

Vanessa Joan Müller, November 9, 2025, at the MAK

© MAK/Kathrin Pokorny-Nagel

The book, to include the artist’s book, is in the first place a storage medium for texts and/or images. It is characterized by the way it structures and arranges these texts and images and by its choice of typeface. It organizes pre-existing material—texts and images—in a layout that follows certain conventions—conventions that it is also free to ignore.

There is, however, one kind of text that in this respect is considerably less flexible than others, since the way it appears on the book page, on the sheet of paper, is to a great extent determined by its inherent nature. This special case is the poem. In its classical form—of secondary interest here—it is structured in lines and verses. In its experimental form, on the other hand, its arrangement of lines and letters also highlights the field on which it is located—the page with its white substrate contributes to the constitution of meaning through language. This substantively charged white space creates a productive blurring of sign and meaning, signifier and signified, that may result in total dissociation and discursive breakdown. All that then remains is a negative space that can be suggestively saturated with meaning.

In 1967, Franz Mon, a protagonist of Concrete Poetry, wrote in his text “zur poesie der fläche” [on the poetry of surface]: “A written text serves us best the less its optical dimension strikes the eye. Of its arrangement on the surface we demand at most harmonious imperceptibility.”[1] He elaborates: “Just as surface is exterior to text, so typeface is secondary thereto.”[2] In a poem, on the other hand, this unconditionality is rejected; the surface of the page becomes a conscious, positively charged space. The white space on the page becomes part of the text, actively contributing its semantic features, such as center, margins, head, foot, right, left. The text, finally, forms an abstract image that is as much a part of the production of meaning as that which the text itself articulates. Since the 1960s, these quasi texts-become-images have laid claim to a broad field of artistic poetry—as a wide range of image poems attempt to connect poetry to conceptual art.

Before we undertake a very brief foray through what has been subsumed somewhat vaguely here under the term “experimental poetry,” we nevertheless need to address the question as to what this term actually means—and not only in the visual arts. Of course, one of its characteristics is the free arrangement of words; but since Modernism, poetry has encompassed so much more, referring fundamentally to a language that, beyond its communicative function, highlights its own formal structure, its tonal dimension, and its appearance as text on the page—thus actively reflecting on both its semantic and aesthetic dimensions. It is language become image or performatively extended into three-dimensionality, language that escapes direct legibility or even invents itself anew. This poetic function of language is articulated both in everyday discourse and in works located on the interface between text and image, text and performance.

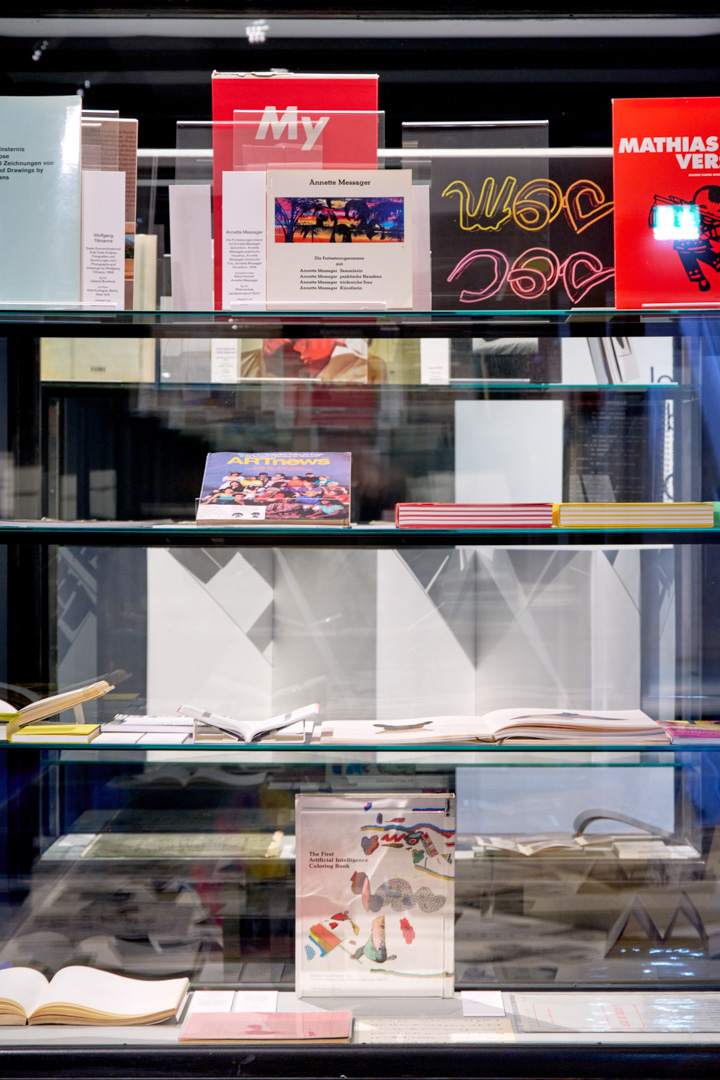

MAK Exhibition View, 2025

TURNING PAGES: Artists’ Books of the Present

Central Room MAK Design Lab

© MAK/Christian Mendez

For the linguist Roman Jakobson, who recognized and named this poetic function of language, incorporating it into his epoch-making model of linguistic communication, language is characterized by the fact that, using various aesthetic-stylistic and aesthetic-rhetorical strategies, it turns linguistic communication into a reflection on language and its contents itself—whereby the focus is on the linguistic sign per se that manifests a formal structure deviating from everyday communication, for instance by the use of rhetorical strategies or by a conspicuously syntactical structure. For Jakobsen the special characteristic of “poeticity” is that it transposes “the principle of equivalence from the axis of selection to the axis of combination.”[3] What for purposes of comprehension is normally formulated or verbally expressed using sentence structures whose meaning is more or less fixed is in poetic language politely ignored in favor of new, unexpected combinations. What Jakobsen does not mention—because in the final analysis he is indeed interested in language as a model of communication—is the aesthetic-visual level, on which the word appears as written or printed, in its typographic form. But what is of primary significance from our perspective is when the visual level of the text is juxtaposed with its phonetic and semantic levels—as complement, extension, suspense, or negation.

An early example of the latter—one frequently cited as a pioneering example of this fundamental transformation of word to image and one that still today possesses something close to cult status—is Stéphane Mallarmé’s 1897 poem “Un coup de dés jamais n’abolira le hazard.” It is the apogee of Symbolist poetry, but above all it is an activation of the word in visual form. Individual lines of the poem are drawn out over several pages, thus massively spacing out its text. The lines’ irregularity and scattered nature cause them to form images, and the surrounding white space on the page is also strongly semanticized.

Radically committed to Modernism, if not a proto-structuralist, Mallarmé believed that the poet should fully subordinate his discourse to language, such that it is the latter that facilitates its own utterance. Language thus emphasizes the space that makes relationships within words and their unfolding on the page possible in the first place. “Un coup de dés” is a paradigmatic expression of this idea: the reader’s gaze doesn’t simply wander from left to right along the letters but focuses on the page as such, and then in a second step—as it were following a visual impulse—begins to read. Mallarmé took a lot of care in selecting his typefaces and font sizes. He thus achieves a visually perspectivist effect, while on the level of semantics the lines are charged with meaning according to their size on the page. But aside from their horizontal and vertical extension, the pages possess an imaginary third dimension that escapes the material level of the book, namely that of the empty white space surrounding the letters. Through this white space, this productive void, Mallarmé finally claimed his place in the history not only of literature but also of art.

For in 1969 Marcel Broodthaers, himself a poet turned artist, took Mallarmé’s poem and transformed it into an abstract graphic surface by overwriting Mallarmé’s words with black negative space. He deliberately selected a version of Mallarmé’s book in which the typeface was already restrained and the font size homogenized. He then published his own edition of the result, one in which it is not words that unfold across the surface of the page but only black lines and bars, corresponding to the font sizes and line lengths of the original. Broodthaers so to speak deleted the words and replaced them by the blackness of negation. Lines of verse became abstract lines, and the white of the page became definitively a compositional element. And Broodthaers replaced Mallarmé’s own categorization of his work as “Poème” on the book’s cover with the word “Image”.

Already in his final volume of poetry, before he resolved to become an artist, Broodthaers applied a strategy of partially overlaying his text with areas of color. His Pense-Bête (1964) is characterized by systematic interventions in the text that exasperate any reading of it, if not forcing us to give up the attempt altogether in favor of interpreting its pages as text-image compositions. Broodthaers programmatically took the last surviving copies of this book as material for his first sculpture, thus rendering them completely illegible. This strategy also demonstrates that negation often has the power to fashion the material that serves as the starting point for such late Modernist poetic deconstructions—just as contemporary poststructuralist theory frequently explored “writing degree zero”, the death of the author, and overlaying the written text with the interpretative act of reading as constructive rereading. From then on, the text has become what one makes of it.

There exists a further version of Mallarmé’s work by Cerith Wyn Evans—a form of homage to both Mallarmé and Broodthaers (Un coup de dés jamais n’abolira le hasard, 2009). (Indeed there exist a great many variations of Mallarmé’s book, testifying to the significance of this free-floating poem.) Cerith Wyn Evans resolutely goes one step further than Broodthaers, eliminating the black bars from the latter’s book and turning the pages’ punched-out surfaces into a porous object; these consequently leave the book to be displayed as a series of single framed pages. Cerith Wyn Evans thus takes the emancipation of language even further, for here language no longer strives to be the signifier of an external signified but characters with an aspiration to autonomy. Deleting letters, words and sentences by striking or cutting them out also opens up new possibilities—poetry commits itself to negative space, thus bringing about the renewal of indeterminacy. It fashions for itself new creative spaces beyond logocentric relationships, that still exist in the more avantgarde varieties of language-based poetry.

MAK Exhibition View, 2025

TURNING PAGES: Artists’ Books of the Present

Central Room MAK Design Lab

© MAK/Christian Mendez

Achieving such a degree zero opens up new opportunities. The 1960s and 1970s are full of experimental poetry in which the visual quality of language is explored and autonomized—particularly in so-called Concrete Poetry, that disengages typeface from meaning, pits them against each other, or stages them as a redundant, self-referential system. Fruitful examples of the poetic function of language in our latitudes are provided by the Vienna Group, in particular by Gerhard Rühm, who in the early 1950s composed sound poems in which tonal expression was presented as an isolated linguistic gesture. Such transcribed tonal gestures conceptualized the genre of poetry, reducing it to vocal slurs. But at the same time Rühm sought in a different direction to test linguistic expressiveness by juxtaposing unrelated words in chance combinations, and thus to recreate in part what had once been called a poem. Individual words thus still possess semantic and phonetic potential, as in classical lyric poetry, but are reduced to mere surface, as it were alienated from themselves. Even though Rühm, as did many others, creates “text images” by arranging letters and words on the page, in his work writing and image oscillate without ever achieving clarity.

There exist innumerable such typograms and optical poems, often composed on a typewriter or made up of collaged fragments cut from newspapers and magazines. As works on paper, often framed, they assume the status of an artwork, but one that has abandoned the book to circulate in channels other than those of the classical visual arts. As such it has much in common with the informal exchanges of Mail Art, as existing in particular in the countries of the former Eastern bloc.[4] One of the many great artists of this movement is Jiří Valoch from Brno who, using a minimalist vocabulary, has in numerous ways explored the correlation of space and language. His small editions of self-produced booklets and visual poems, posted in special envelopes, helped to foster transnational exchange during the Cold War while avoiding state controls—a subversive form of communication, political in nature despite its abstract formalism.

In the USA there also arose in the late 1960s, in parallel with Conceptual Art, typographic poems and abstract visuals created on the typewriter. An important forum for this art form was the magazine 0 to 9, self-published between 1967 and 1969 by Vito Acconci—also a great fan of Mallarmé—and his sister-in-law Bernadette Mayer. Originally appearing in cheap, duplicated, stapled editions, the magazine consisted mostly of language-based and conceptual contributions by artists and poets—semi-written operations in a poetic space that eschewed the referential function of language. Readability was not a criterion, and the letters’ often anarchistic vividness made even the contemporary word-and-image compositions of the European avantgarde look comparatively tame. This was partly because the latter movement was situating itself more strongly within literature. Acconci, on the other hand, consciously strove to fashion a new, quasi dematerialized do-it-yourself exhibition context outside of existing art galleries and magazines. He published works by among others Sol LeWitt, Robert Smithson, Robert Barry, John Giorno, Dan Graham, Lee Lozano, Adrian Piper, Yvonne Rainer, Lawrence Weiner, and Steve Paxton.

What is striking about this list? That it consists primarily of male artists, and that the few women in it are performance artists. In Europe one also finds very little Visual or Concrete Poetry by women; contemporary anthologies are sometimes completely devoid of women’s work. Without wishing to overstate this gender-specific aspect, it nevertheless cannot be overlooked when we turn to the second big field of poetic text production, one that emerged in the 1960s following a general opening up and rapprochement of artistic disciplines—what Theodor Adorno once called an increasing “fraying at the edges.” Language became performative. In its emphasis on the phonetic quality of language, poetry—lyric—aspired to be read aloud or even performed, an aspiration that Visual Poetry, by the way, resolutely resists by privileging language as a visual system of letters as opposed to conceptional reading. The sound of words, the rhythm of verses, of word combinations, on the other hand, are all primarily articulated when language is activated on the phonetic level. For a long time, public performances of poetry possessed a veneer of bourgeois respectability—something not particularly conducive to experimental appropriation. But prompted by Fluxus and other manifestations of fine art moving in the direction of literature, performance, and above all music, this genre too was ripe for a radical rereading.

Thus, in the context of a new, voiced poetics, the word finally became part of a disembodied, hybrid text production. Following feminism’s second wave, such experiments with embodied language also frequently involved reformulating identities and drafting an alternative to a binary perspective on the world. By retreating from the coherence of an identity-based determinism, performative language was once again freed from narrative mechanisms. Existing identitarian linkages, adjustments, constrictions, role assignments, and categorizations were either dissolved in linguistic performance or newly formatted.

Katalin Ladik, a Yugoslav-Hungarian, multimedia artist, poet, and Vocal Arts performer, whose work is conceptually rooted in the multiethnic avantgarde of former Yugoslavia, experimented early on with language, presenting the results independently of the book. For her, comprehension functions beyond national languages and classical logocentric categories. Ladik radically uses her voice as both instrument and medium, modulates the sounds of letters, and—precisely from such radically limited material—produces an enormous excess of connotation. Her well-known work O-pus provides the soundtrack for an experimental video by Attila Csernik; it can also be performed live. In the video the letter O is liberated from paper and wanders through cinematic space until finally it assumes a floating, immaterial, primarily tonal existence. In her 2023 exhibition in the Haus der Kunst in Munich, Ladik again activated the work, this time unfolding its visual notation along the museum’s staircase. Instructions for the speech performance—in which the letter O is repeated nine times, with pursed lips and vibrating vocal chords, followed by a short pause before the “pus” is gently enunciated—seem simple enough, yet the result resembles a conceptual operatic aria.[5]

MAK Exhibition View, 2025

TURNING PAGES: Artists’ Books of the Present

Central Room MAK Design Lab

© MAK/Christian Mendez

Which brings us to a fundamental question: how do we talk about something that deliberately subverts the discursive meaning of conventional language? Even the degree zeros that characterize all hitherto mentioned language arts with their roots in Modernism are not infinitely variable. Moving to our own immediate present, we also notice that many works are again becoming more narratively inclined—without therefore succumbing to the classical logic of sense. Take for instance the example of Nora Turato, as representative of a younger generation that resolutely follows Ladik’s example—though substituting for onomatopoeia associative fragments of the language which, unbidden, inundates us through digital media. Turato appropriates slogans, scraps of conversation, and text fragments, processing them as performances, in book form, and also in murals and video installations, to create repetitive litanies that condense the essence (and nonsense) of algorithmized everyday communication. Dematerialized and haunting digital space, language is here on the one hand incarnated, without the subject itself actually speaking, and on the other hand manifests itself in a space in which its banality generates its own semantics.

Somewhere between the desire for authenticity and the compulsion to uniformity, this recycled language has not only saturated the texture of the urban landscape but also the people who move through it. Embedded in the world of commerce and digital self-presentation, Turato’s work resolutely illuminates their functioning and performance, combing through feeds, accounts, news pages, and lists, creating scripts that serve as material for wall-filling paintings and performances. Turato’s often half-hour long monologues are carefully choreographed and rehearsed, whereby she uses her voice—trained with the help of a voice and dialect coach who works with actors—in a similarly multifaceted way to Ladik before her. Her wall and text pictures, on the other hand, remind us of works by such artists as Barbara Kruger, once more raising conceptual questions of copyright.

Hanne Lippard is another contemporary language performer in the art field, although she actually uses only her voice—live or in sound installations—as her medium, presenting it in specific architectonic situations. In their appropriation and repetitive modulation of existing material, her narrative sequences aim directly at what Roman Jacobsen has described in his function of language. In her resorting to the clichés of everyday language, Lippard so to speak observes life through the filter of the social media, manipulating these through syntactic repetition and disassociation, through intonational shifts or using homonyms, thus remolding them into melodic abstractions. Just as does Turato, she retraces the rise of digital communication, showing how the latter reprograms our relationship to language. Her focus on the conscious and unconscious automatization of language creates connotative ambiguities and, potentially, misinterpretations, but it also aims at semantic evacuation.[6]

Then again, installation-based language (at the other end of the spectrum to a poetics extending into three-dimensional space) does not necessarily present itself as a decipherable slogan, as a wall poem. Barbara Kapusta’s work, which may serve here as example, is indeed the result of many years exploring the relationship between body and language, between materiality, language and architecture. Her black vinyl letters do indeed enter into a relationship with three-dimensional space, suggesting imagistic lettering. But in the final analysis they remain uninterpretable. Even so, Kapusta consciously uses the term “linguistic bodies”—bodies inhabited by an idiosyncratic volition and immune to normative archetypes. In her large-format murals—created in part using a unique alphabet written in flames—language-based text presents itself as fundamentally ambivalent, also implying linguistic queerness. Her cryptic symbols embody English words or whole sentences that refer to forms of togetherness, to exchange. After all, every linguistic system has its own rules and thus exclusions. But a purely visual, seemingly figurative language that has abandoned classical legibility subverts such preexisting structures. And indeed, the title of a work such as A New Fiery Community (2024) can only be “understood” so long as we accept that letters are but one form of symbolic language among many, and that visual sensations may indeed fall within the purlieu of semiotics.

To summarize: visual poetry, and later the visualization of the word in three-dimensional space, strove for ambivalence and, frequently, negation—seeking out the disruptive moment of language’s communicative function, deconstructing it, and assembling it anew. It is an abstraction indebted to late Modernism, to the attempt to approach degree zero. It involves rethinking semantics by partially deleting it, thus freeing up new potential through the very gesture of negation. Its chief concern is the multiplicity of meaning contained in redundancy—overwriting content that is then reformed in imaginary negative space—or the pure anarchy of language that, freed from logic and grammar, achieves sovereignty in the form of an aesthetically exorbitant alphabet salad.

The performative activation of language, on the other hand, is premised on freeing the infinite potential of subjective articulation. Interestingly, in materializing tonality, there nevertheless seems to be a predilection for juxtaposing the written version of a performance with its activation, as if pointing out the fundamental difference between perceiving and subjectifying a seemingly objective notation system. When language becomes pervious to images and music, to the visual and the acoustic—when it largely emancipates itself from utilitarian conventions and strives to enter material or immaterial space—then this too constitutes an attempt to find a new linguistic orientation in a radically changed world.

This latter aspect gains even more in urgency in an age in which AI is advancing inexorably into the realm of text production. For where the poetic function of language reigns supreme, it can also incite rebellion—at least according to Franco “Bifo” Berardi in his book The Uprising.[7] In his analysis of our thoroughly economized present and its alleged absence of alternative strategies, he proposes poetry, of all things, as a subversive tool of resistance. A full-blooded Italian post-Marxist, in the wake of the recent financial crises Berardi argues that the actual worth of objects or activities is becoming increasingly irrelevant to their market and monetary value. All aspects of life are forced to obey a common exploitative logic, resulting in a crisis of culture and social imagination. Neoliberal deregulation has decoupled financial transactions not only from state controls but also from material production, creating a self-referential system. Something similar is happening to language: at the latest since the Symbolists, language has disengaged from prevailing contexts of meaning and no longer necessarily refers to things and people; it has become a hermetically closed symbol system. Just as Symbolism experimented with separating the signifier from its denotative and referential function, so financial capitalism has separated monetary signifiers from their reference to physical goods. Signifier and signified have become as decoupled from each other as have money and commodity, exchange value and use value.

For Berardi, poetry thus offers a return to semantic candor, an invitation to transcend the fixed meanings of words. Grammar usually serves to define those boundaries that outline a communicative space. And today economics is a universal grammar that pervades all levels of human activity: language is subject to the dictates of economic exchangeability, limited to communicating information, integrated into the techno-linguistic automatisms of its social usage.

Berardi’s strategy is, consequently, to fashion a new form of autonomy from this alienation. Against the expropriation of language by the logic of financial capitalism—that forces all social relationships to be interpreted as market concepts—he opposes poetry with its never completely controllable linguistic excess: “Poetry is language’s excess: poetry is what in language cannot be reduced to information, and is not exchangeable, but gives way to a new common ground for understanding, of shared meaning: the creation of a new world.”[8]

According to Berardi, the symbolic aspect of language has already been usurped by capitalist semantics. And digital technology is more than ever determined to abolish the unique expressive power of polysemy, gesture, and voice in favor of a language that is subject only to a linguistic machinery. Alluding to Symbolist poetry, Berardi thus evokes the physicality of language, its pureness of form beyond content, that together hinder its being transformed into a commodity. Algorithms do not understand poetry, and AI can only produce bad copies thereof. Poetic language thus also involves occupying communicative space with words that evade economization, with non-exchangeable language—the return of writing’s sensual power.

[1] Franz Mon, „zur poesie der fläche“ [on the poetry of the surface], in: Konkrete Poesie. Eine Anthologie von Eugen Grominger [Concrete Poetry: an Anthology by Eugen Grominger], Stuttgart 1972, 169.[2] Ibid.[3] Roman Jakobsen, „Linguistik und Poetik“, in: id., Poetik. Ausgewählte Aufsätze 1921–1971, [“Linguistics and Poetics”, in: id., Poetics: Selected Essays 1921–1971], Frankfurt am Main 1989, 94.[4] See the lecture by Diedrich Diederichsen: Lecture by Diedrich Diederichsen on Artists’ Books – MAK Blog[5] Here is a video documentation: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=la7TJ4z83Ao[6] Examples of Hanne Lippard’s audio works may be found on the artist’s website: https://hannelippard.com/[7] Franco “Bifo” Berardi, The Uprising. On Poetry and Finance, Los Angeles 2012.[8] Ibid., 147.

The exhibition TURNING PAGES: Artists’ Books of the Present is on view in the Central Space MAK Design Lab until 22 March 2026.

A contribution by Vanessa Joan Müller, curator and author.

The blog article is part of the interdisciplinary Creative Europe project AbeX.

This project is supported by Creative Europe.

The exhibition TURNING PAGES: Artists’ Books of the Present, along with its supporting program and the accompanying publication, is part of the interdisciplinary Creative Europe project AbeX, funded by the European Union.

Views and opinions expressed are, however, those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Education and Culture Executive Agency (EACEA). Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.

Really engaging piece—loved how it highlights poetry moving beyond words into visual and spatial expression. The exhibition shows how language can be experienced, not just read, in fresh and imaginative ways.

Fascinating article! I enjoyed learning how experimental poetry transcends traditional text and becomes visual and spatial art, especially in the context of the TURNING PAGES exhibition. It’s inspiring to see language explored in such creative and unconventional ways.