31. März 2021

00000001 TAW at the MAK DESIGN LAB

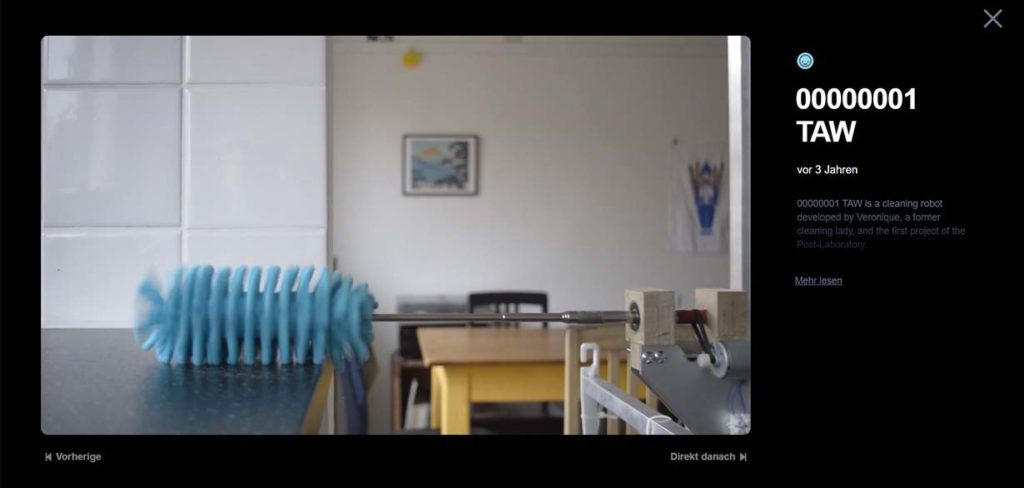

The Leipzig based designer and design researcher Ottonie von Roeder is represented in the MAK DESIGN LAB with her project Post-Labouratory, which shows the cleaning robot 00000001 TAW (2017) developed by Veronique N. For the MAK blog, she introduces the robot.

This is 00000001 TAW. Instead of waiting for visitors at the MAK DESIGN LAB or cleaning the MAK secretly at night, 00000001 TAW is supposed to perform Veronique N.’s former job as a cleaner while she is travelling around the world. Veronique was the first to automate her labour as part of the Post-Labouratory, a project developed in 2017 by Ottonie von Roeder.

MAK DESIGN LAB

Ottonie von Roeder, Post-Labouratory, 00000001 TAW (2017)

© Stefan Lux

You might own a robotic vacuum cleaner or dream of a self-cleaning toilet. Robot technologies are becoming part of our daily lives and are changing our working environments substantially. Robots are progressively performing jobs previously conducted by humans. According to the research paper The future of employment: How susceptible are jobs to computerisation (University of Oxford, 2013) by Carl Frey and Michael Osborne, forty-seven per cent of current jobs are likely to be automatable over the following twenty years. The likelihood of the automation of a cleaner’s job in the next fifteen years is fifty-seven per cent. In the past technological development created new industries and therefore new kinds of jobs. In their book Inventing the future: Postcapitalism and a world without work (London and New York, 2015) Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams argue that the current wave of automation is running so fast that most of us will not be able to keep up with the necessary skills. If our prevailing systems remain unchanged, we will be facing a social crisis. Precariousness will increase and an undesirable dystopia could become reality – an economy in which all automating technology is owned and operated by one per cent of the population, while the remaining ninety-nine per cent would either be unemployed or could do the leftovers of non-automatable labour.

Link zum Video Ottonie Roeder (vimeo.com)

Instead of seeing the automation of labour as a threat, the Post-Labouratory suggests to embrace it as an opportunity to re-negotiate the value of labour and work. Ideally, automation and a new social system will allow us to spend more time with the things we enjoy. In the beginning of the project Veronique found it very difficult to imagine that a robot could do her job and to think of what she would like to do when she didn’t have to work for an income anymore.

In the nineteen-eighties the philosopher Frithjof Bergmann introduced the “6 months – 6 months proposal” to counter the loss of fifty per cent of the jobs in the automotive industry, which was due to automation. He suggested that the workers work half of the year and spend the other half with more exciting things. The workers refused the proposal not knowing what to do with the freedom in prospect. Bergmann described this as a ‘poverty of desire’, a ‘societal ill’ that people do not know what to do when asked regarding true calling. The labour we do is such a vital source of status and identity that it is tough for us to face a mental liberation from employment. Such a proposal implies a significant cultural shift and questions how we would exist without labour.

In her book The Human Condition (University of Chicago Press, 2013) the philosopher Hannah Arendt distinguishes between work and labour, two words for what we have to come to think of as the same activity. Labour, on the one hand, is a cyclical, repeated and partly futile process. Labour is the main way we acquire an income, create an identity, economically contribute to society and make social connections. According to Arendt, it has become an unreliable source of such credits for many. Therefore, labour is experienced as meaningless and tiring, performed mainly out of necessity. Work, on the other hand, is the defining activity of humanity. The output of work is a durable object that becomes part of the world we live in. Work includes the opportunity for creativity, collaboration and satisfaction. It lets us participate in society and can be the gate to autonomy.

- 00000001 TAW and Veronique N. © Femke Reijerman

- 3 first robots of Post-Labouratory © Femke Reijerman

During the collaboration with Veronique, it became clear how creativity and involvement empowered her to question her current job situation and to open up her mind towards a post-labour future. In a video at the MAK DESIGN LAB Veronique tells how she explored her desires during the development of the robot and what she is doing in her post-labour life while 00000001 TAW is working for her income.

A contribution by Ottonie von Roeder, designer and design researcher based in Leipzig.