27. Oktober 2022

ENTANGLED RELATIONS—ANIMATED BODIES: Sonja Bäumel on the Austrian Pavilion at the 23rd Triennale Milano

The artist Sonja Bäumel is currently representing Austria at the 23rd Triennale Milano International Exhibition (Milan, 15 July–11 December 2022) with her performative and multisensory installation ENTANGLED RELATIONS—ANIMATED BODIES. MAK Curator Marlies Wirth, Curator of the Austrian Pavilion, talks to her about the artistic and scientific background of this year’s spectacular entry for Austria.

Under the motto Unknown Unknowns. An Introduction to Mysteries, this year’s International Exhibition directs visitors’ attention to the manifold unknowns of the technological, biological, and climatic changes of the past decades. Commissioned by the MAK and funded by the Federal Ministry for Arts, Culture, the Civil Service and Sport of the Republic of Austria, Sonja Bäumel explores the limits of the human body and its vital relationship to the microbial world. ENTANGLED RELATIONS—ANIMATED BODIES makes us wonder and think what it might mean if the human-made borders around the body and our understanding of the human self were expanded.

By unfolding, shifting, and fragmenting the so-called “body boundaries” of human bodies, the work draws attention to the interdependence between moving, seeing, and touching bodies and their constant exchange with microbial milieus, revealing unrecognized forms of movement, intelligence, and communication.

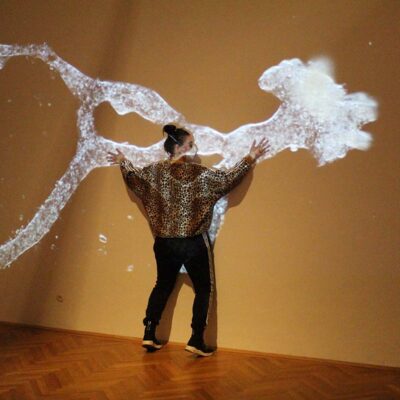

Installation view of the Austrian Contribution ENTANGLED RELATIONS – ANIMATED BODIES to the 23rd Triennale Milano International Exhibition

An installation by Sonja Bäumel, commissioned and curated by the MAK – Museum of Applied Arts, Vienna

© Gianluca Di Ioia/MAK

MICROBIAL WORLD

Marlies Wirth: The 23rd Triennale Milano International Exhibition has chosen the topic of Unknown Unknowns to look deep into the multifaceted aspects of our world – our planet, our universe, or our own bodies – a world, to which we have remained partially and irresponsibly blind over the past decades. While the main exhibition is curated by the astrophysicist Ersilia Vaudo and the architect Francis Kére, and is looking deep into the universe, the Austrian Pavilion revolves around the invisible universe within ourselves, the microbial world.

Thousands of microbes like bacteria, viruses and other species that co-exist and communicate with our bodies and are so to say “entangled” with the human life. It has become almost common knowledge that “fifty percent of cells forming our body are not human, but microbial” and that our bodies co-evolve with microbes which live on our skin and in inside our bodies, the microbiome is also sometimes referred to as our “second brain” (the gut).

What are some of the lesser known facts about microbes that you find fascinating? How do they influence human behavior? Why is it so important to acknowledge these other intelligent and communicative life forms?

Sonja Bäumel: Indeed, Western science has recently come to understand ancient indigenous wisdom that the human body comprises twice as many bacterial cells as human cells, living both in and on our bodies. “Although this fact usually does not really affect our self-recognition directly and is not a threat to our identity, an awareness of it definitely alters the way we think of our bodies, as they no longer can be perceived as sealed vessels, but rather as trans species environments” (Bakke Monika, Practicing aesthetics among nonhuman somas, in: Practicing Pragmatist Aesthetics, Critical Perspectives on the Arts, Edited by Wojciech Małecki, Brill, 2014, pages 153–168, pg. 155). Our bodies are mostly bacteria, viruses, archaea, eukaryotes, yeast and parasites. For our simple existence we depend on the cooperation of different life forms, within, on and surrounding our bodies. Without them, we could not exist. Mitochondria, the energy power plants of our cells, were created hundreds of millions of years ago from microorganisms. We are symbiotic multi-beings, created from the gigantic, bubbly and vivid liquids on planet earth. We are multitudes of different cells, of different beings, of the same cells, of the same beings, as part of a shared planet.

These ideas and forms of knowing human embodiment were formulated decades ago by the American evolutionary theorist, biologist, author, educator, and public speaker Lynn Margulis.

It is clear that this “new” type of awareness might offend us in regard to our desire for autonomy and environmental independency, as some societies might wish to look at their human existence as sterile, not having to worry about biological complexity. However, it has been proven that human bodies, on average, carry around three kilos of bacteria, most of which are found in the intestines. Hence, one could ask the question: Who nurtures whom? Or, who depends on whom? Rooted in such fundamental questions, my work seeks to stimulate cultural imagination regarding the impact deriving from a deep understanding of the microbial entanglement we are immersed in, and the related paradigm shifts deriving from such awareness. To be capable of assimilating with biological non-human life systems – which is a necessary call in the face of environmental emergencies/developments – we need to consider and respect microbes and other tiny creatures as equal partners. Microorganisms have successfully adapted to radical changes and transformations in their ecosystems. They are capable of evolving in relation to their needs. We can learn from their expertise in behavioral change, acquired through billions of years of existence.

I am especially fascinated by what this means for the expansion of the so-called “self”, beyond the singular, as always multiple and many; and by what influence the language of microbes, known scientifically as “quorum sensing” might have on non-linguistic communication and its related collective actions. In science, this field of investigation was initiated more than thirty years ago and its societal and political potential is still to be fully unraveled. According to their population density, microbes can alter their behavior using an intercellular signaling molecular process. By way of quorum sensing microbes are effectively aware of one another’s presence; they count themselves and behave as a multi-cellular group. The microbes we depend on dissolve trans species boundaries and exhibit as yet unexplored forms of intelligence. In other words, there is an urgency to recognize microbial life forms as actors that co-shape our bodies (and thus our physical and mental conditions). Particularly, if we aspire to experience and thus better understand inter-organismic communication, as it may allow us to better take care of microcosms, and thus ultimately to better take care of ourselves and our environment.

Installation view of the Austrian Contribution ENTANGLED RELATIONS – ANIMATED BODIES to the 23rd Triennale Milano International Exhibition

An installation by Sonja Bäumel, commissioned and curated by the MAK – Museum of Applied Arts, Vienna

© Gianluca Di Ioia/MAK

ANATOMY / BODY

Marlies Wirth: Before your career as an artist and researcher you have studied fashion (in Austria) and conceptual design (in the Netherlands). The human body has always been at the center of your thinking and making. But how did you work and perspective shift towards “working with the living” and live bacteria in your earlier work, later also using your own body for experiments?

Starting your research for the Triennale installation, you looked at anatomical representations of the human body from different times and cultural contexts – what is so striking about those and how would you like to see the future change?

Sonja Bäumel: Through active collaborative endeavours, I investigate the influence that scientific knowledge has had on the way we perceived and interpreted the human body historically, and how such formerly generated, yet still rather predominant views, affects current (mainly Western) society and the cultural contexts in which we act. Since fourteen years I have been (and will continue to work) with microbial bodies. I have mostly shown them alive, growing and decaying, which posed a challenge to the conditions of public institutions and musea through not knowing how to deal with living artworks.

For the Triennale installation, I wanted to take other risks and thereby challenge myself by using as yet unused materials and techniques to create a mysterious and imaginary world; and to conceptually oppose the seeming contradiction of life: dead representations of human bodies: anatomical models, as cultural and media theorist Maaike Bleeker pointedly expressed wrote “one of the central paradoxes of anatomy (is) the use of dead bodies to teach about living ones” (Bleeker, Maaike, Martin Massumi, and The Matrix, in: id. (ed.), Anatomy Live: Performance and the Operating Theatre, Amsterdam, Amsterdam University Press, 2008, pg. 151–164, 151). Is it not absurd that we start learning about our bodies through anatomical models, which are always singular, sterile, outside of social and political context, static, mainly masculine and focused mainly on our visual senses? Are living bodies not all about bubbling and buoyant liquids, about growth and composite senses, about transformation, movement, presence, and absence? Therefore, we decided for the Triennale project to unsettle representations of static bodies by celebrating the ephemeral and the animated body through performance in a stage setting. At the same time, we aimed to illuminate the collapse of static epidermic and trans-species boundaries, as an invitation to start exploring what it means to be multitudes.

COLLECTIVE WORK & AMOEBA

Marlies Wirth: You have been working with the world of microbes and living bacteria since more than 10 years now, always in long-term collaboration with scientists or other transdisciplinary practitioners or artists.

Cooperation and collaboration in a collective way is usually part of your artistic practice. For this installation, you chose the amoeba as a “representative” of the microbial world. It is present in various was – as a 40.000 times enlarged sculpture and as a dynamically moving projection of a living amoeba.

For the realization of the Austrian contribution at Triennale you cooperated with scientific and artistic partner institutions such as the University of Applied Arts’ Science Visualization Lab and Studio Book and Paper, but also the ISTA – Austrian Institute of Science and Technology with the Sixt Group who work on cell biology and immunology.

Which collaborations were involved in the process of producing the installation, why are amoeba the perfect example of “collective bodies” and what is the connection between amoebic and human immune cells?

- Work with Vitalie Leşan © Sonja Bäumel

- Work with Vitalie Leşan © Sonja Bäumel

Sonja Bäumel: Our complex future can only be shaped through collective processes and support structures; the mode of working collectively is therefore an important part of a project. My experience as an artist has taught me that public institutions often fail to recognize these shared modes of (artistic) production and treat them as insubstantial for the artistic results/exhibition. In the past, I was often wondering where collaborative support for artists should come from, if not from the most prestigious cultural institutions. Could a museum or gallery exist at all without the shared efforts of artists, curators, thinkers, organizers, craftspersons, technicians, etc.? As artists we should more openly exchange, share and claim our rights as well as our skills in collaborative processual labor. This is one of the reasons why I specifically wanted to work with colleagues as well as support freelance artists such as: Vitalie Leşan, Doris Uhlich, Wim van Egmond, Martha Ruess, Nina Ober and Eva Mahhov, who all contributed their diverse expertise to our project. Moreover, the aim was to combine forces and expertise between scientific and artistic institutions such as MAK and ISTA (Institute of Science and Technology Austria), in order to facilitate future collaborations for young practitioners with an interest in ArtScience projects.

- Work with Doris Uhlich © Sonja Bäumel

- Probing the dynamically moving projection of a living amoeba by Wim van Egmond © Sonja Bäumel

- Sonja Bäumel and Martha Ruess experimenting with silicone © Sonja Bäumel

The Science Visualization Lab of the University of Applied Arts Vienna, Alfred Vendl and Martina R. Fröschl, contributed a micro-tomographically scanned dataset of an amoeba. This data was used to create a 40,000 times larger-than-life sculpture of an amoeba.

- Sculpture of an amoeba © Sonja Bäumel

- Mario Kojetinsky and team, test setup MAK Forum, March 2022 © Sonja Bäumel

Beatrix Mapalagama from the Studio Book and Paper at the University of Applied Arts Vienna contributed important material input with her paper experiments, and she established the contact to Vitalie Leşan. He is one of the rare remaining professionals who are able to produce huge sculptures out of papier-mâché and more. The choice for this material was connected to the reference to early anatomical models which were made out of paper; to work with recycled materials found in our surrounding felt liberating, especially the use of newspapers, which resulted in an act of literally shredding daily information and re-cycling it. The low-cost papier-mâché moreover served the project with one of its important properties: tactility.

- ENTANGLED RELATIONS – ANIMATED BODIES process images. © Sonja Bäumel

- ENTANGLED RELATIONS – ANIMATED BODIES process images. © Sonja Bäumel

- ENTANGLED RELATIONS – ANIMATED BODIES process images. © Sonja Bäumel

The choreography was developed in collaboration with Doris Uhlich, which allowed us to celebrate the ephemeral and the animated body through her impressive performance. A dynamic projection of a real amoeba by Wim van Egmond overlays the installation and is accompanied by sound transmitting the bubbling vitals of the microbial world, which was developed in collaboration with Eva Mahhov. The graphic design was made by Nina Ober.

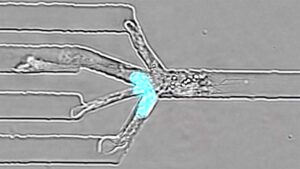

Responding to your other questions, the project is animated by the ability of amoeba to alter their shape by extending their liquid skin and thereby to blur where an “individual” begins or ends: “[Social] amoebas queer the nature of identity, calling into question the individual/group binary.” (Barad, Karen, Intra-actions, interview of Karen Barad by Adam Kleinmann, in: Mousse Magazine 34, 2012 [issue on dOCUMENTA (13)], pg. 76–81, 77). The Sixt Group at the ISTA – Austrian Institute of Science and Technology conducts path-breaking research on immune cells. Like amoeba, most cells in our body are also motile. Our immune cells do not only look like amoeba when we observe them under the microscope; they also use the same cytoskeleton molecules in order to fuel the transformations of their cell body; they also use these molecular mechanisms to smell molecular signals exuded by other cells. In other words, cells as well as our bodies are shaped by their environment: in water these organisms are called amoeba, in our bodies’ immune cells, both made out of the same substance. Entangled Relations— Animated Bodies aims to make the inseparable and seemingly inexistent entanglements and relations among bodies and their ecosystems (human and more-than-human) visible, tangible, walkable, wearable, recognizable, readable, and changeable.

Experiment on immune cells by the Sixt Group at the

ISTA – Austrian Institute of Science and Technology

© Sonja Bäumel

PERFORMANCE

Marlies Wirth: The installation encompasses all our senses somehow: the visual, the aural, the tactile senses through different textures and a soft floor, the movement and ephemerality in the performance by Doris Uhlich and through the “entanglement” of it all when visitors engage with the work inside the Austrian pavilion.

The choreography for the performance was developed by you and Doris Uhlich who performed live during the opening of the exhibition – tell us more why you chose the medium of performance to be part of the project and about the different interactions between the human body (of the performer) and the elements of the installation.

Sonja Bäumel: I am convinced that the human body can only be represented in and through aliveness and movement. Hence, performance appears to be the most suitable approach for actualized, contemporary, dynamic corporeal “models”.

This is the second collaboration between Doris and myself. In our first collaboration, in 2019, we developed and performed together at the Frankfurter Kunstverein for the project “microbial entanglement”. I enjoy working with Doris, I admire her sensibility, and we share a deep understanding for each other’s work; we give ourselves space within a project and are both process-driven artists.

Furthermore, I believe that we have to rethink our relationship with environment and other-than-human life forms, to hear their voices and interests so we can take them into account. My work is motivated by the belief that we must urgently look for, experiment and account for diverse multi-beings languages, and awaken and sharpen our many forgotten senses. In order to do so we should understand ourselves as tiny earthlings within a much larger earthly cosmos. In our performed installation we aim to show our view by working with the confusion of scale, as I believe that our ethics are strongly linked to a false understanding of the greatness of human race. The large amoeba sculpture makes the human body appear small, vulnerable and fragile. That is the intention.

- Amoeba travelling to Milan © Sonja Bäumel

- Fragile human being © Sonja Bäumel

By unfolding, shifting, and decomposing the so-called “body boundary,” the performance intends to speak through movement about the evolution as well as the restriction of our bodies through outdated representations of the human bodies. It explores ways of coming closer to other-than-human life forms. The “anatomy” of a human body here cracks and breaks open. Within such a context, the boundaries of the human body dissolve and skin becomes blurry and fluid, suggesting that the human figure is never to be considered singular, but continuously shaped by and interdependent on its environments. It expresses the potential for enlivening the anatomical model as a performative walking biotope, engaging the imaginary and the factual in a mutual dialogue.

The conversation was conducted by Marlies Wirth, Curator, Digital Culture and Design Collection, MAK